The Monoid and Monad Architectural Patterns

Objects have much in common with the monads of Leibniz.- Alan Kay

There are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.- C.A.R. Hoare

One of the biggest problems that exists in software engineering today is uncontrolled complicatedness. The size and complicatedness of libraries, applications, and systems has continued to grow exponentially while at the same time, the number of libraries, applications, and systems grows. The patterns for this week exist to help reduce this complicatedness at all of these levels, both those of size and those of number.

The previous readings all dealt with patterns for individual functions. This week, the patterns are regarding how to have groups of functions that can work together more cleanly, with less complicatedness, and more beautifully. The two groups for this week are monoids and monads.

A monoid is an organized bunch of functions that follow a few simple rules. The bunch of functions

The word bunch was chosen specifically. It implies some sort of association that isn't used in common programming parlance like list, set, or collection are. You can have any type of bunch, and as long as the functions in the bunch follow the rules for being a monoid, the bunch of functions is a monoid.

The mathematical description of the group of functions is that it is a semi-group for which there is an identity value. Some of the rules listed above are inherited since any monoid is a semi-group.

You've composed functions A LOT up to this point in your life in the code you've written. Week 05's map-filter-reduce example is just one time out of many when you've done so. Any time you have called a function and then passed the result of that function call to another function or operator, you have done composition.

Say you had two functions, \(g\ ::\ a\rightarrow a\) and \(f\ ::\ a\rightarrow a\). If you call \(g\) and then pass the result to \(f\) you've composed the two functions. You may have used an intermediate variable when you've done this, or maybe you didn't. It makes no difference. You did function composition.

Here is one common way to express that composition. \(f\circ g\). Now, if you think about it, \(f\circ g\) could be thought of as just another function. You could have written one function and included the code from \(f\) and \(g\) in it. It would, more than likely, be bad to do so...but you could have. So you can view \(f\circ g\) as if it was a function named \(h\) and \(h\) would be equivalent to \(f\circ g\), or stated more succinctly, \(h\equiv f\circ g\). Remember that \(g\ ::\ a\rightarrow a\) and \(f\ ::\ a\rightarrow a\). It then follows that \(h\) has a parameter of type \(a\), a value of type \(a\) and a declaration of \(h\ :: \ a\rightarrow a\). As \(h\equiv f\circ g\), it follows that \(f\circ g\ ::\ a\rightarrow a\).

It is common among programmers to compose functions where the values of the functions are different. You've done this before. Maybe you started with an \(Integer\) and, after having used two or more functions ended up with an \(Float\) or some other sort of change. It is not OK for functions in monoids to have non-matching types. You could have a monoid and then pass the results of chaining several of those monoidal functions to one that has a different value type. That way your functions can compose without issue. But what about meta-data?

Monads are all about meta-data. Meta-data is data about the data. For example, consider the list \([1,2,3,4,5]\). One piece of meta-data describing the list is its length, \(5\). Another could be its average, or its sum, or anything else that is important to know regarding lists in your application.

As pieces of data move through your application, meta-data about them can be passed with them if the data and the meta-data are included together in some combined type like a 2-tuple, 3-tuple, n-tuple, dictionary, list, tree, etc. One common piece of meta-data is whether a computation worked or failed. Examples of needing this meta-data could be when you are accessing data from or storing data in untrustworthy locations such as databases, users, files, or any other data source. These data storage and source items are side effects, though monads can be used for much more than dealing with side effects.

Since users, databases, web access points and any other type of input or output are all side effects and are all untrustworthy it would be nice to know if the request for storage or access of data worked or failed. You can write a monad type a and a set of functions who's values are the monad type to help you more readily deal with this situation. Monoids just can't pull that off. Another ability of any monad you create is the functions that are part of that monad can be combined together in an way that is similar to function composition.

Let's first look at monad consisting of a generic monad type and a set of single parameter functions who's value is that monad type. As you read earlier, a monoid has a description like this \(f\ ::\ a\rightarrow b\). A function that is part of a monad has a description that looks like this \(f\ ::\ a\rightarrow Mb\). There is that small but very important change from \(b\) to \(Mb\). What does that change mean? What is the meaning of \(M\)?

Those are two very good questions. Let's start by defining \(Mb\). In the above example, \(Mb\) is some type of wrapper, of your choice, around \(b\). The \(Mb\) could be a 2-tuple, a 3-tuple, a n-tuple, a dictionary, list, or any other containing type as discussed earlier. \(Mb\) is specific to the need and is designed and written by you. It may be the result of accessing a database to build the \(Mb\). It may be the result of getting data from the user to build the \(Mb\). It may be the result of code that calculates meta-data from the data and builds a \(Mb\). It can be A LOT of different things.

For functions in a monoid, their value is a direct computation resulting from the value of the parameter. For functions in a monad, their value is a wrapped element \(Mb\). How these functions do this varies depending on what the types of the parameters of the monadal functions. Reread the two previous sentences many times until you understand the difference..because they are significantly different.

Consider the 3 functions below, \(f, g,\text{ and }h\), that are part of a monad.

\(\begin{align*} f\ &::\ a\rightarrow Mb\\ g\ &::\ b\rightarrow Mc\\ h\ &::\ c\rightarrow Md\\ \end{align*}\)

Notice that it appears that you might be able to compose these functions together. That appearance is a lie.😱 They can't be composed because composition requires the value of the first function to match the type of the second. The monad type \(Mb\) is not the same type as \(b\). Therefore, \(Mb\) can not be passed to \(g\ ::\ b\rightarrow Mc\), regardless of what \(Mb\) does under the hood. Composition is out! What, then, can we do to link these functions together in a way somewhat similar to composition with monoids?

For a monad to be a monad, the functions making up the monad must be closed under what is called binding. To make it easier to understand binding, we'll use this symbol, \(\ggg \), to represent binding.

Consider the functions \(f,g\), and \(h\) above. Binding these three functions would result in the following situation.

\((f\ggg g\ggg h)\ ::\ Ma\rightarrow Md\)

Its as if there was a function that had a parameter that was \(a\) and had a value that was \(Md\), though no such function exists. In this way it is similar to function composition.

Notice the similarities and differences between binding and the composition of three similar monoidal functions. \((f\circ g\circ h)\ ::\ a\rightarrow a\)

One major difference is that functions bound together have as their value a monadal type, not just a raw computed value.

What then does the function declaration look like for this mysterious bind function? Well...monads have to be designed for specific situations. Let's design a bind function for a monad that helps us deal with successful vs unsuccessful computations. Let's call this set of monadal functions and the maybe monadal type the maybe monad. Let's have the monad type for maybe be a 2-tuple where the first tuple element is either \(ok\) or \(fail\) indicating success or failure. All the \(\lambda\)s used with this monad are required to return \(nil\) if they fail. Bind, in this case, is then

\(\begin{align*} -spec\ maybe\_bind\ ::&\ Ma\ \lambda\rightarrow Mb\\ \\ maybe\_bind\ ::&\ \{fail,data\}\ \_\lambda\rightarrow \{fail,data\};\\ maybe\_bind\ ::&\ \{\_,data\}\ \lambda\rightarrow\\ &result \leftarrow \lambda(data),\\ &case\\ &\quad result = nil\rightarrow\\ &\quad\quad \{fail,\lambda,data\}\\ &\quad otherwise\rightarrow \{ok,result\}. \end{align*}\)

The value of the \(maybe\_bind\) function is a 2-tuple indicating success and and 3-tuple indicating failure. Success and failure are determined by the \(\lambda\)s which are also part of the maybe monad.

For maybe to be a monad, there must also be an \(id\) function(see the rules below) that wraps raw data in a monadal type. For the maybe id function is

\(\begin{align*} -spec\ maybe\_id\ ::&\ a\rightarrow Ma\\ \\ maybe\_id\ ::&\ a\rightarrow\\ &\{ok, a\}. \end{align*}\)

for any \(a\) of any type.

These functions are fine and dandy, but look what it would look like to use them. Imagine that a is a URL string. The code to bind the three functions \(f, g, \text{ and } h\) in that order with the URL is this.

\(maybe\_bind\ ::\ (maybe\_bind\ ::\ (maybe\_bind\ ::\ (maybe\_id\ ::\ \text{"http://www.somename.com"}) f) g) h\).

Ughhh! That's a variation of the example of ugly code from week 05!😨 Also, since the monad could consist of any number of functions, not just the three in this example, using \(maybe\_bind\) gets even uglier to use as more functions are bound. Let's fix it by applying the same solution we used in week 05. Chaining!🥳

Let's make a version of the chain function that can be used with any monad we choose to create in the future and call it \(monad\_chain\). In the pseudocode below, let \(bind\) be the binding function for a monad and \([\lambda]\) be a subset, proper or improper, of that monad's lambda functions.

\(\begin{align*} -spec\ monad\_chain\ ::&\ Ma\ bind\ [\lambda]\rightarrow Mb\\ \\ monad\_chain\ ::&\ Ma\ \_\ []\rightarrow Ma;\\ monad\_chain\ ::&\ Ma\ bind\ [\lambda\mid t]\rightarrow\\ &monad\_chain\ ::\ (bind\ Ma\ \lambda)\ bind\ t \end{align*}\)

This version of chaining resolves the issue of needing to check the value of each function called prior to executing the next function, an ugly anti-pattern used in many applications, libraries, and code sets. Instead, when the \(maybe\_bind\) algorithm is used by \(monad\_chain\), if a failure occurs no unnecessary calls to \(\lambda\)s after a failure.

The code to use this version of chain with the maybe monad example is much cleaner.

\(monad\_chain\ ::\ (maybe\_id\ \text{"http://www.somename.com"})\ maybe\_bind\ [f,g,h]\)

Remember that conceptually, bind being applied to these three functions can be represented as \((f\ggg g\ggg h)\ ::\ a\rightarrow Md\) and that the end result of the binding is some monadal type, \(Md\).

As mentioned at the beginning of this reading, reducing the complicatedness of libraries, applications, and systems is the purpose of the monoid and monad patterns.

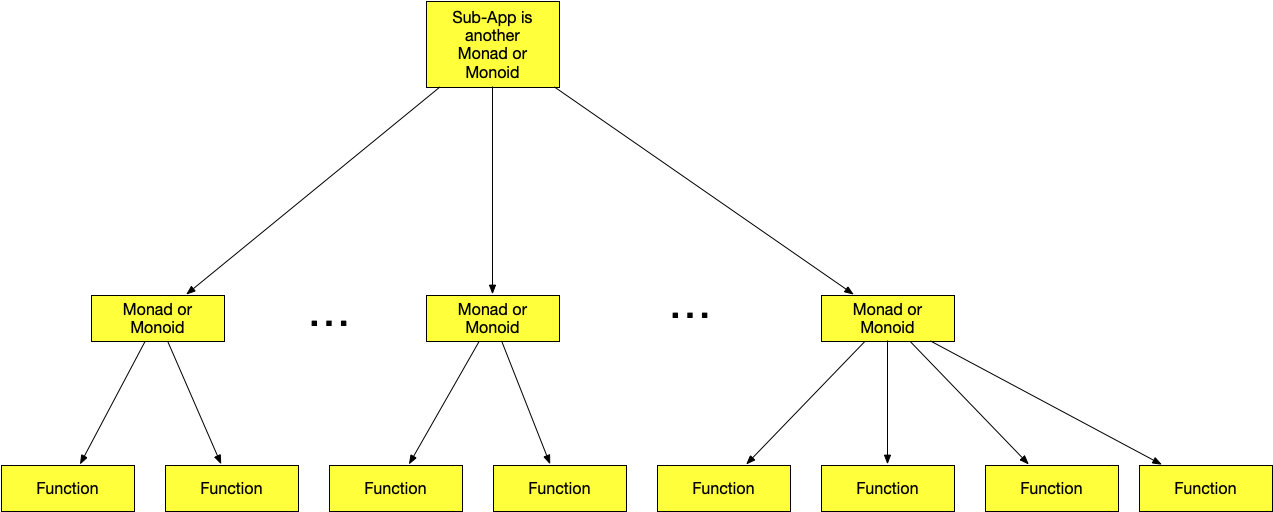

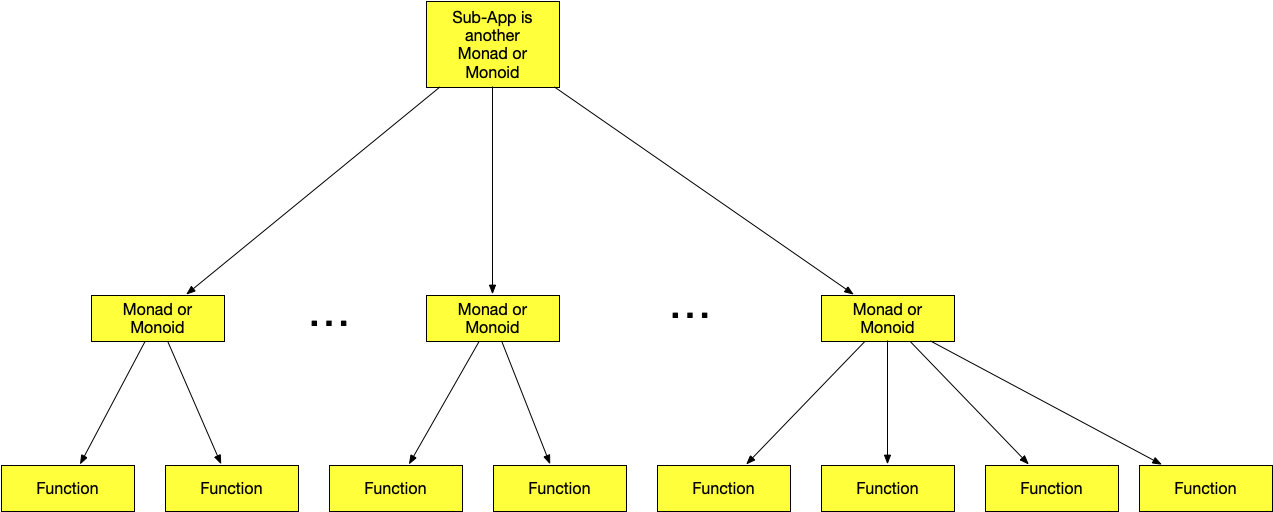

Consider Figure 1. Any sub-appliction, a logically consistant portion of an appliction, can be designed as a monoid or monad that binds together other monoids or monads. To do so, there must be a set of moniodal or monadal functions of the higher-level monoid or monad that use, via composition or binding, the functions of the underlying monoids or monads.

Following this architectural pattern, another sub-app can be designed as a monoid or monad that uses, via composition or binding, the functions of the other underlying sub-app monoids or monads. But the pattern doesn't end there. Applications can be designed as monoids or monads using, via composition or binding, any number of sub-apps. It also follows from this pattern that sub-systems, systems, sub-networks, networks, and inter-networks can all be designed to be monoids or monads using, via composition or binding, functions of their underlying monoids or monads.

We have explored this pattern from the bottom up. If we consider it from the top down, any inter-network, network, system, sub-system, application, or sub-application you create can be recursively designed as some combination of monoids and/or monads. Each level dealing only with a minimal amount of complicatedness.

Think about this non-technical analogy to this architectural design. There are managers who take all the complicatedness of knowing about and dealing with every decision and interaction of all the employees they manage, be that one or multiple levels down. These managers are known by the epitaph of micromanagers. Invariably the complicatedness overwhelms them and they are less effective than they could be. But there are managers that take a very different approach.

These managers trust their subordinates to make decisions that those subordinates can handle and for which they have responsibility. This type of manager's job is much less complicated and they tend to do a better job, as do all of those who work as subordinates, as long as this delegation of responsibility pattern is maintained by all of their subordinate managers.

If each level of monoid or monad in an inter-network or other larger or smaller type of interacting assemblage is designed appropriately, each monoid or monad will delegate responsibility for doing appropriate work to its sub monoids or monads. Therefore, each level of any monoid or monad, from inter-network to the lowest-level substituent monoid or monad becomes much more self-documenting. Each also is only as complicated as need be, and the overall complicatedness is decreased.

For the Computer Science version of both monoids and monads, there are rules that can be applied to determine if a something is one, the other, or neither of these patterns. While these rules are often expressed in an arcane way, explanations of the rules are included here to make them easier to apply.

A group, collection, set, etc. of functions is a monoid if;

For any two functions in a group, collection, set, etc., there is a composition rule such that the composition of the two functions is also in the group, collection, set, etc. The group, collection, set, etc. is closed under composition.

Any set of compositional rules for the group, collection, set, etc. of functions must obey the law of associativity.

There must exist some identity function such that composition of any element of the group, collection, set, etc. with the identity produces the original function.

A group, collection, set, etc. of functions is a monad if;

There is a composition-like function called bind.

The bind function has as parameters a monadal type \(Ma\) and a function that has parameters of type \(a\) and a value of type \(Mb\). The value of bind is an \(Mb).

The bind function must obey the law of associativity

There is a unit function that doesn't change a raw value. It just wraps it to make it a monadal type.

There is a video on monoids and monads by Brian Beckman available.