W02 Case Study Reading: Requirements Elicitation at Aviation Companies

Instructions

Prepare for your team meeting and your individual analysis by thoughtfully reading the following case study.

Submission

After completing the reading, return to Canvas to submit a quiz about the basic case study facts.

Then, in separate assignments, you will discuss this case study with your team and complete your analysis of it.

Case Study: Requirements Elicitation at Aviation Companies

The specific characters, companies, and projects of this case study are fictional, but they are based on actual circumstances that occurred at aviation companies.

Roberto Diaz

12:00 pm - Lunch in the Park

Roberto froze, his sandwich completely forgotten, eyes fixed on the words glaring back accusingly from his smartphone.

"Ethiopian Officials Say Faulty Boeing Software Played Role in Deadly 737 Max Crash" footnote

He clicked the headline and continued reading.

"Ethiopian investigators said a flawed flight control system triggered by faulty sensor data, is at least partly to blame for last year's crash of a 737 Max airplane operated by Ethiopian Airlines. All 157 people on board were killed.

Roberto looked up and stared at nothing, his worst nightmare realized on the screen in front of him. As a software engineer specializing in avionics, Roberto knew first hand what it took to build and certify flight control systems. The few bites of sandwich he had eaten soured in his stomach.

Roberto had designed and written software for several other planes in the 7x7 line. While he knew his work was good, excellent actually, he couldn't help wondering if his software was partly to blame. He shook his head. The 737 Max wasn't his. Morbid imaginings like that weren't helpful. Besides, he had a meeting to get to. If he didn't leave now he'd be late.

1:00 pm - All Hands Meeting

Roberto walked into the room just as the meeting started. Several other people were already sitting around the gleaming conference table. He moved quickly and sat down next to Jake Williams, a software engineer and close friend.

"Have you seen this?" Roberto whispered, turning his phone toward Jake.

Jake shook his head and pointed to the mosaic of faces projected on the far wall. The loud, disembodied voice of Karen Peterson, vice president of MotionTech's Hydraulic Systems Division, penetrated the silence.

"It looks like everyone's here so we'll get started."

Roberto was barely listening. It was his first video conference since rejoining the company. Everything seemed the same. And yet, something was different. He discretely looked around the room. As far as he could tell they were the same people, sitting in the same chairs, watching the same screen. A rise in Karen's voice caught his attention.

"We really need to keep a close eye on the 787!"

That was the difference. Writing flight control software was serious work. The MotionTech he knew was systematic and calm. Now, a new sense of urgency, a real intensity, filled the air. Something Jake said earlier in the day came flooding back into Roberto's mind.

"We've lost a lot of time. We really need you Roberto!"

Rejoining MotionTech was a bit of unexpected good luck. Two years ago, when he'd been offered a more senior position at Standard Controls, or SC, he thought leaving was the right thing to do. It wasn't long before he wished he hadn't. When Karen contacted him two weeks ago and asked him to come back to MotionTech, he was ready.

Roberto's mind wandered, settling on the first meeting he ever attended at MotionTech. It was the 747 upgrade. Back then, John Haskell, a senior engineer, sat at the head of the table, his laptop screen projected on the wall behind him. He was reviewing software requirements.

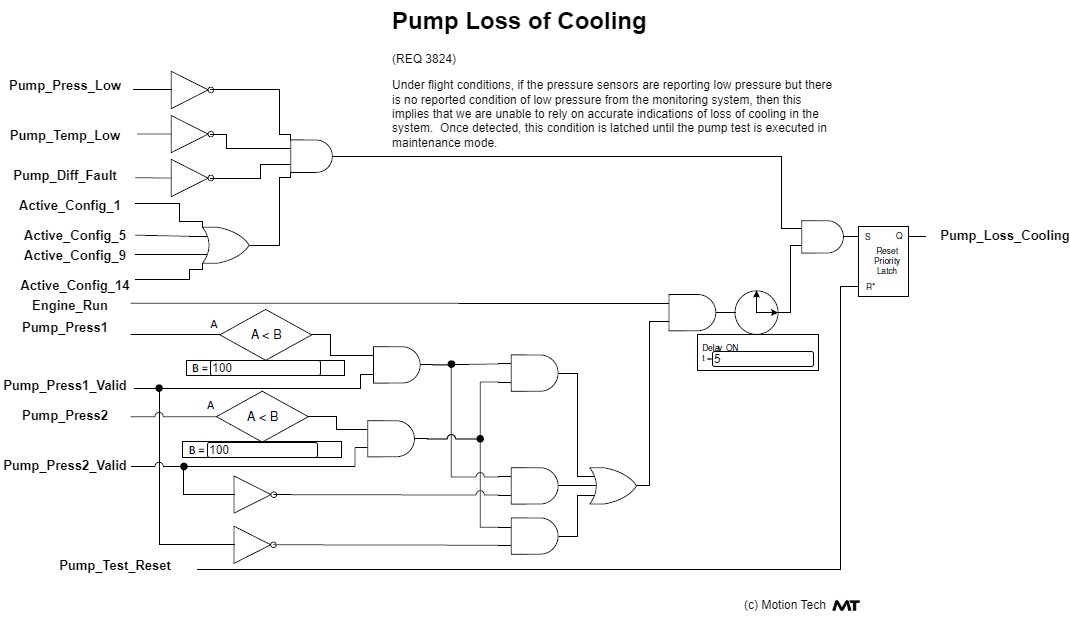

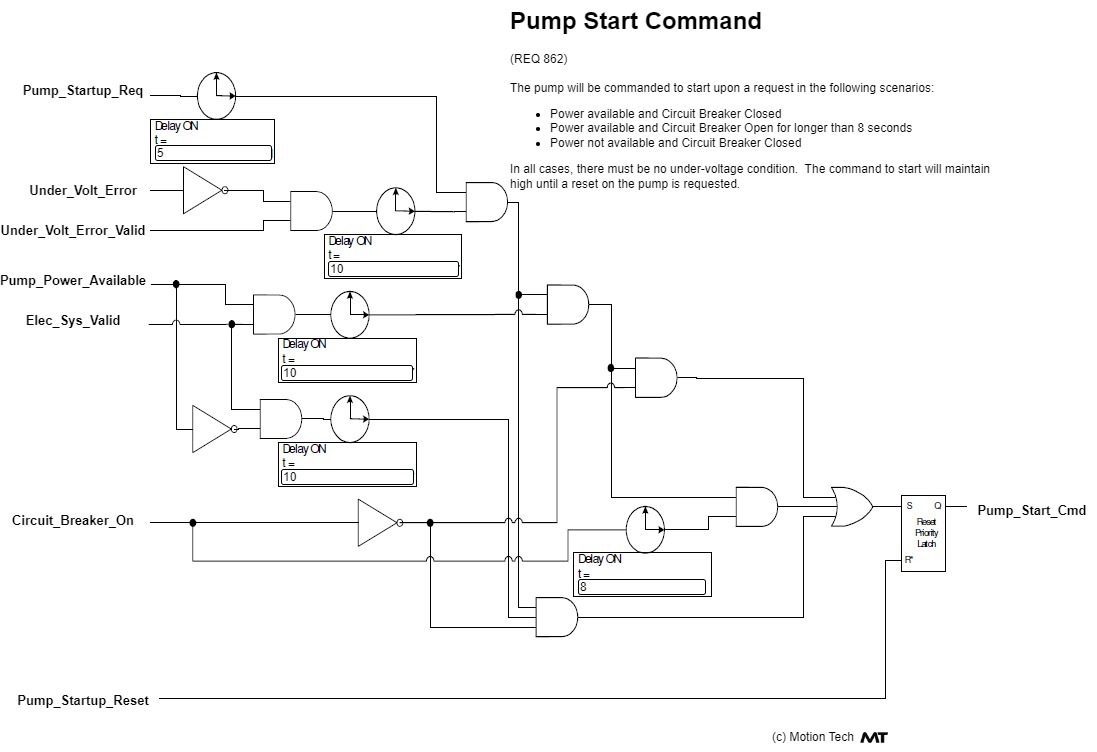

Roberto remembered his surprise as John explained the logic diagrams (see Exhibits A-B). They were nothing like the software requirements specification he'd learned to write at university. They looked more like electrical circuits than anything. They made a lot of sense though, when he learned to read them. Turns out none of the other software engineers knew how to read them either. Once they figured out the symbols and notation though, they grew to love them.

Roberto smiled to himself. The Outside Boeing Air-worthiness Representatives, or OBARs as they were known, who also attended their meetings, never embraced the diagrams quite like they did. They always wanted them translated into written form. Even pseudo-code was better as far as the OBARs were concerned.

In Roberto's mind, there was real clarity in the diagrams. Translating them into a software design was simple. Writing the C code and testing it was straightforward as well. In fact, you could trace the information in the diagrams directly through all the project phases and deliverables if you wanted to. The same ideas and vocabulary found in the requirements appeared everywhere. The quality assurance engineers loved it.

It wasn't all bliss though. There were hundreds of diagrams to understand before they could even think about making the software. Some of them were small and simple. Others were large and complex. Some had dozens of inputs and outputs. Worse than that, they were constantly changing.

Roberto's smile faded as he remembered trying to identify and document the many requirements changes. Because of the graphical nature of the diagrams, there was no way to automate the process. The best anyone could do was print and manually inspect them, comparing every shape, line and annotation in the old diagrams to the new. He wondered how many extra weeks all that work added to the original schedule.

The 737 Max article forced its way to the front of Roberto's mind, his stomach reacting again. He thought about the terror those people must have experienced and closed his eyes. "How could this happen?" he agonized silently.

Responsibly, reliably, cost effectively. That was the company's motto. If MotionTech was about anything, it was standards and processes. All software at MotionTech, from level A to E footnote, was treated with the same kind of thoroughness and attention to detail. A failure like the 737 Max seemed impossible.

Something in Karen's tone brought his mind back. There was the same urgency again. Roberto forced himself to focus on her words.

2:00 pm - Hallway Conversation

"Sorry about earlier," said Jake. "I read the article yesterday. They think it was MCAS."

"MCAS?"

"Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System," Jake explained. "A couple of sensors sent conflicting data, activating MCAS, which repeatedly tried to push the plane's nose down."

"Why didn't the pilots shut it off?"

"They did the first time," Jake replied. "They brought the nose back up and then turned everything on again. Same thing happened but they couldn't regain control. They hit the ground at 40 degrees going 500 feet per second."

Roberto thought about the sensor data. The DO-178C safety standards required all avionics systems to operate predictably, even if sensors failed or provided conflicting information. There's no way MCAS would have passed testing if it couldn't. Unless, of course, the standard wasn't specified in the requirements. He couldn't be sure but there didn't seem to be any other explanation. Roberto considered the implications of that thought a moment longer.

"Are you listening to me? Jake interrupted.

"Sorry about that," Roberto replied. "It's just hard to imagine how it could all go so wrong."

They turned down the hall together, making the rest of the walk in silence.

"See you at three," Jake said, leaving Roberto at his office door.

3:00 pm - 787 Status Meeting

Roberto threaded his way through the other people in the room to a chair near the head of the table. Most of his days were filled with meetings and today was no different. Jake was already in his seat near the middle. Brian Jackman, the project manager, abruptly stood up and started to speak.

"Ok everyone, let's start. Most of you remember Roberto Diaz. He's been at SC for the past two years but now he's back." Brian paused to smile at Roberto before continuing, "Let's look at the schedule."

Roberto cringed inside. Everyone knew the situation with the schedule already. MotionTech sometimes hired other companies to write parts of the software they made. SC was one of them. Unfortunately, they were often late, putting MotionTech further and further behind.

He remembered his excitement when he was offered the job as a software architect with SC. He enjoyed helping clients discover their needs and, if he was honest, deciding what path to take. It was so satisfying to frame the technical standards, fit the pieces together, and see the solution through to the end. How could he have known what it would actually be like?

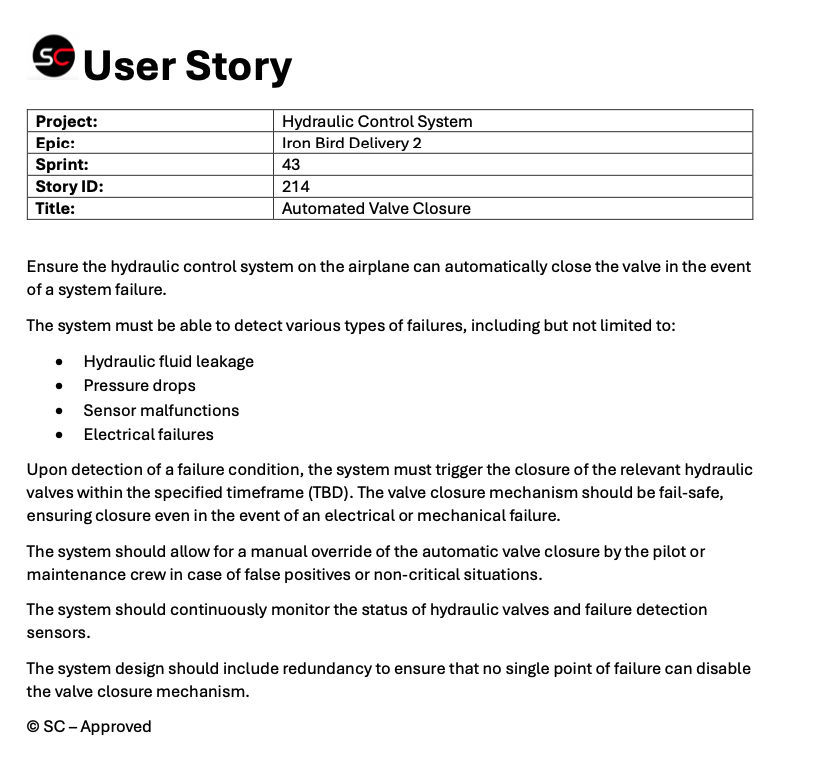

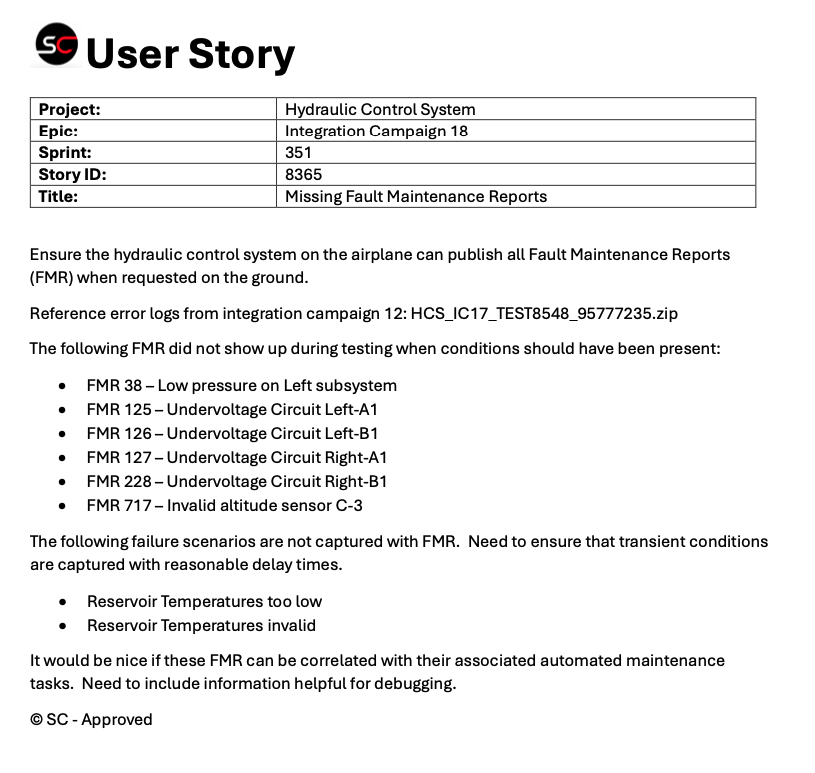

They worked differently at SC. For one thing, the logic diagrams he was familiar with were replaced by sprints and user stories (see Exhibits C-D). It was understandable, he supposed. Agile techniques were all the rage, and, remembering how hard it was to update requirements at MotionTech, seemed to fit the situation well. footnote

The shapes and lines were all gone, replaced by simple line items in an online Jira backlog. Roberto remembered his reaction as he clicked the first one. "As the… I want… so that…," he read to himself. Seemed pretty straight forward. He scrolled further and continued reading, "Acceptance Criteria." That was strange. The heading was there but no detail. The rest of the screen was blank.

"If only I had known," he thought wryly.

The user stories were liberating at first. Their brevity promised great freedom. The engineers could choose for themselves how to implement each feature. Roberto had to admit, they really knew a lot about operating systems and drivers at SC. It made sense to leave the details up to each engineer.

It wasn't long before they seemed like a prison though. Roberto knew that agile wasn't the problem. It was the teams' attitude toward requirements that made things hard. The Jira backlog made scheduling seem like a waste of time. So they didn't make one. Individually owned user stories made collaboration seem unnecessary. So they never bothered.

It's not that they didn't work hard. They just never seemed to finish. The development engineers seemed caught in an endless loop of refactoring, each one searching for the perfect implementation of their assigned feature. From Roberto's perspective, none of it produced any real difference in the final product. The list of completed work rarely changed.

And the few times it did, the quality assurance engineers didn't follow through. They were good engineers, so why didn't they? Roberto paused for a moment. Maybe it had something to do with the acceptance criteria. In retrospect it made sense. If you didn't specify when a feature was complete, how could you test it? Roberto's mind returned to his time at SC.

They were on a death march with no foreseeable end. He even stopped going to the one-on-one meetings with Wil, his boss. There didn't seem to be any point. More than that, it was emotionally draining. Wil was never angry, after all, there was always another sprint, but Roberto felt the failure keenly.

He shifted uncomfortably as he remembered the very last meeting at SC. Many stakeholders including line management, product management, and several customers were there. The quality assurance and testing teams were conspicuously absent. Feeling more embarrassment than ever, Roberto stood up and began, "Here's what we were supposed to do..."

He remembered the depth of his despair later that night as, alone in his backyard, he looked up into the night sky and pleaded with God to give him another job.

A flicker at the front of the room caught Roberto's eye, bringing his mind back to the people in the room. Brian was standing in front of the screen, gesturing at some of the dates. Roberto shifted his focus to the present meeting.

4:00 pm - One-on-one With Karen

"Glad to have you back," said Karen.

Roberto leaned across the desk to shake the outstretched hand.

"Glad to be here," he replied.

"I'll get right to the point," she continued as they sat down. "I hired you because we need help with the 787. More than that, we need someone who can help us make sure we never, ever, have a repeat of the 737. I assume you've heard about it."

Roberto nodded.

"I know it had nothing to do with hydraulics, but we're all taking a long, hard look at ourselves. Add to that our scheduling problems and we've got a real tough situation." Karen paused for a moment.

"One thing's for sure, we need to be more agile. We don't have a lot of time to begin with and we lose even more dealing with logic diagram changes. Maybe it's time to start thinking about sprints and user stories. What do you think?" she asked.

Roberto raised his eyebrows. Karen continued before he could answer.

"I can't imagine what those last moments were like on the 737. Maybe our current processes are too overbearing. Maybe we've lost sight of something in all of it. I actually just read an article about how DO-178C actually leaves a lot of space for agile." footnote She paused once more and looked carefully at Roberto.

"How do you think we should document our system requirements? Take a day to ponder it and let's talk again."

Roberto stood up and thanked Karen. One day wasn't a lot of time. What should he recommend, and just as importantly, why?

Exhibits

Footnotes

- David Schaper, Brakkton Booker, “Ethiopian Officials Say Faulty Boeing Software Played Role in Deadly 737 Max Crash,” NPR, March 9, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/03/09/813740173/ethiopian-officials-say-faulty- boeing-software-played-role-in-deadly-737-max-cra (accessed January 23, 2024). Back to content ↩

- The Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification, or DO-178C, classifies software into five levels based on the consequences of failure: (A) critical, (B) hazardous-severe, (C) major, (D) minor, and (E) no effect. More critical systems typically undergo more rigorous verification and validation. Back to content ↩

- Many mainstream companies, including some in the aviation industry, were successfully using agile methodologies in their software engineering projects. See “Using Agile Methodologies in Aerospace”, Boston Consulting Group, October 28, 2019, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/agile-methodologies-aerospace-interview-latecoere-serge-berenger (accessed February 1 2024). Back to content ↩

- The DO-178C is most often associated with waterfall or v-model processes and documentation. However, some industry experts read the guidelines in a different way. See Mikhail Sudbin's article, “Why DO-178C Forces Software Development To Be More Agile,” LinkedIn, October 19, 2015. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-do-178c-forces-software-development-more-agile-mikhail-sudbin (accessed February 5, 2024) Back to content ↩

Other Links:

- Return to: Week Overview | Course Home