W08 Prepare: Reading

Table of Contents

Recursion

Recursive Function Calls

Usually when we write functions, we design them, so they call different functions. Recursion is a technique where a function calls itself. For example, consider the following code:

public void SayHello() {

Console.WriteLine("Hello");

SayHello(); // This is the recursive call

}

This code will print “Hello” forever. Actually, C# will eventually stop with a Stack overflow because the SayHello function was called too many times. Notice that in this function, the first call to SayHello never has a chance to finish. In software, when a function is called, it is put onto a stack. The stack is used to keep track of what function to go back to when a function finishes. In this case, the stack is filling up.

Rules of Recursion

When we use recursion, we need to make sure we follow two important rules:

- Smaller Problem - When we call the function recursively, we need to make sure we are calling the function on a smaller problem. Without this rule, our function will run forever.

- Base Case - As we continue to call the function on a smaller problem, we need a place to stop. We must define a scenario in which recursion is not required. This is called the base case.

Applying these two rules to the SayHello function, we have the following modified code which is keeping track of how many times to say “Hello”:

public void SayHello(int count) {

if (count <= 0) {

return;

}

else {

Console.WriteLine("Hello");

SayHello(count - 1);

}

}

In this new code, the smaller problem is count-1 and the base case is

when count is equal (or less than) zero. When we look at this code, we should probably question the use of recursion when this could have been done with a simple for loop. Recursion should not be used with everything. When used inappropriately, recursion can result is significant performance degradation. However, when used wisely, a simple code solution can be found for complex problems.

Sample Problems - Factorials

Solving problems using recursion requires us to state the solution of a problem in terms of the problem itself (i.e., calling the function recursively). Some problems in mathematics offer good examples of recursion (performance is questionable, but the examples are sound).

A factorial involves multiplying a series of numbers. For a positive integer n (greater than 0), n! (read as n factorial) is defined as n * (n-1) * (n-2) * ... * 3 * 2 * 1. If we wanted to calculate n! using recursion, we need to define the answer in terms of the problem again. The “problem” here is the factorial function. We can rewrite n! as follows:

n! = n * (n-1)!

This solution above satisfies the first rule of recursion. To satisfy the second rule of recursion, we need to define n! for some value of n without using recursion so that our solution does not run forever. Without much math, we can solve 1! and say that it is equal to 1. We now have a base case. With our solution and base case, we can write the code:

public int Factorial(int n) {

if (n <= 1) {

return 1; // 1! = 1 (no recursion)

}

else {

return (n * Factorial(n - 1)); // n! = n * (n - 1)!

}

}

Sample Problems - Fibonacci

The Fibonacci numbers are: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, and so forth. The sequence starts with two 1’s. Each subsequent number is the sum of the two previous values. If we wanted to write a function Fib(n) which would give us the nth Fibonacci number, instead of thinking about loops, let’s define Fib(n) in terms of the same Fib problem but with smaller values:

Fib(n) = Fib(n-1) + Fib(n-2)

If we implement this, eventually we will get to calls of the Fib function with smaller values of n. These smaller values of n represent the base case for recursion solution. Usually we try to think about solutions that we can easily calculate such as Fib(1) which will equal 1. However, if we look at our formula above, we will need more than one base case. Consider n=3 which will require us to use Fib(2) and Fib(1). If we then recursively solve for Fib(2), we will need Fib(1) and Fib(0). In cases like this, we will need more than one base case representing the first two Fibonacci numbers:

Fib(2) = 1

Fib(1) = 1

Our resulting code will be as follows:

public int Fib(int n) {

if (n <= 2)

return 1; // Fib(2) = 1 and Fib(1) = 1

else

return Fib(n - 1) + Fib(n - 2); // Fib(n) = Fib(n - 1) + Fib(n - 2)

}

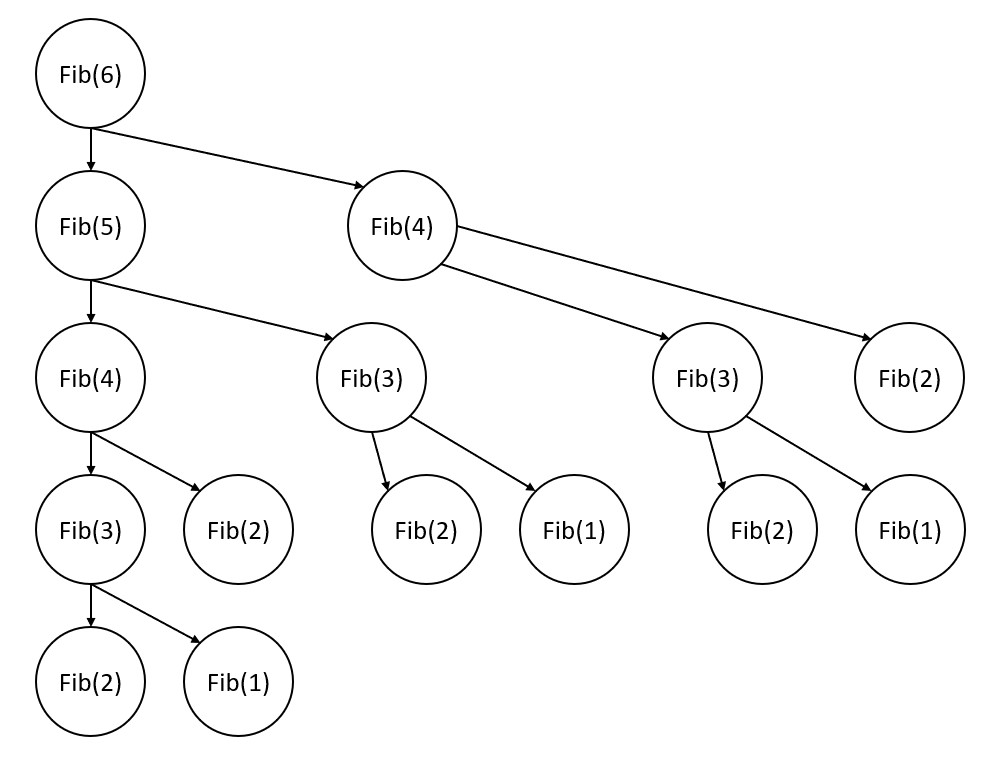

It is a useful exercise to analyze what happens when we call the Fib function. The diagram below shows the functions that are called when we run Fib(6). Notice that the call to Fib(n-1) is called before Fib(n-2) and, therefore, the Fib(n-1) must finish first. Also notice that there are many duplicate calls to the Fib function for the same value of n.

The Fib function was called a total of 15 times! This is an O(2^n) algorithm.

Memoization

We can improve the performance of the Fib function by remembering previous results as we traverse through the recursive call. Memoization is the process of remembering these previous results so that additional recursive calls are not needed. For example, once we discover that Fib(3) is equal to 2, we can store this into a dictionary with a key equal to 3 and the value of 2. This becomes a base case. If we need to calculate Fib(3) again, we will just look up the 3 in the dictionary to get the answer.

The dictionary will only be used by the Fib function and not be returned. Since the dictionary needs to be shared for all recursive calls, we will write code to create the dictionary on the first recursive call only.

public long Fibonacci(int n, Dictionary<int, long> remember = null) {

// If this is the first time calling the function, then

// we need to create the dictionary.

if (remember == null)

remember = new Dictionary<int, long>();

// Base Case

if (n <= 2)

return 1;

// Check if we have solved this one before

if (remember.ContainsKey(n))

return remember[n];

// Otherwise solve with recursion

var result = Fibonacci(n - 1, remember) + Fibonacci(n - 2, remember);

// Remember result for potential later use

remember[n] = result;

return result;

}

...

Console.WriteLine(Fibonacci(1)); // 1

Console.WriteLine(Fibonacci(2)); // 1

Console.WriteLine(Fibonacci(3)); // 2

Console.WriteLine(Fibonacci(4)); // 3

Console.WriteLine(Fibonacci(10)); // 55

Console.WriteLine(Fibonacci(90)); // 2880067194370816120 (This one will

// not work if you don't have the

// 'remember' dictionary implemented).

Sample Problems - Find Permutations

The problem is to calculate the number of ways to reorganize the letters in a word (i.e. the permutations). Mathematically, this should be n! where n is the number of letters in the word. However, using recursion, we can also display each of the permutations (so long as the number of letters is small, otherwise it will take a long time to display all the results).

Let’s assume that our list of letters is [“A”, “B”, “C”, “D”]. Thinking about smaller problems being solved recursively, we could say that the number of permutations would be the sum of the following four things:

- The number of permutations of A followed by all the different permutations of B, C, and D

- The number of permutations of B followed by all the different permutations of A, C, and D

- The number of permutations of C followed by all the different permutations of A, B, and D

- The number of permutations of D followed by all the different permutations of A, B, and C

Each recursive call to the Permutations function will need to know two things: what letters have not been used yet, and the current string that has been built so far. In the four scenarios above, after we add the A, we are left with the letters B, C, and D (the letters that have not been used yet). Additionally, after we add the A, the A should be added to the current string that we have built. The diagram below shows how these function calls will be called and how the resulting permutations will be displayed:

![Shows some of the functions called by Permutations([A,B,C,D]). This first function calls Permutations([B,C,D],'A'), Permutations([A,C,D],'B'), Permutations([A,B,D],'C') and Permutations([A,B,C],'D'). The Permutations([B,C,D],'A') will call Permutations([C,D],'AB'), Permutations([B,D],'AC'), and Permutations([B,C],'AD'). The permutations ([C,D],'AB') will call Permutations([D],'ABC') and Permutations([C],'ABD'). Each of these last 2 functions will call Permutations([],'ABCD') and Permutations([],'ABDC'), respectively. In these last functions, the strings 'ABCD' and 'ABDC' will be printed out in each function respectively.](permutations.jpg)

We also need a base case. The simplest scenario is a list with zero letters. Here is our code:

public void Permutations(string letters, string word = "") {

// Try adding each of the available letters

// to the 'word' and add up all the

// resulting permutations.

if (letters.Length == 0) {

Console.WriteLine(word);

}

else {

for (var i = 0; i < letters.Length; i++) {

// Make a copy of the letters to pass to the

// the next call to permutations. We need

// to remove the letter we just added before

// we call permutations again.

var lettersLeft = letters.Remove(i, 1);

// Add the new letter to the word we have so far

Permutations(lettersLeft, word + letters[i]);

}

}

}

...

Permutations(list("ABC"));

// Results:

// ABC

// ACB

// BAC

// BCA

// CAB

// CBA

Permutations(list("ABCD"));

// Results:

// ABCD

// ABDC

// ACBD

// ACDB

// ADBC

// ADCB

// BACD

// BADC

// BCAD

// BCDA

// BDAC

// BDCA

// CABD

// CADB

// CBAD

// CBDA

// CDAB

// CDBA

// DABC

// DACB

// DBAC

// DBCA

// DCAB

// DCBA

Sample Problems - Binary Search

Recursion plays an important role in several searching and sorting algorithms. The binary search algorithm assumes that the data is already sorted. Just like a phone book, if you had sorted data, then the best way to find something is to look in the middle of the data set. By looking in the middle of the sorted data, we can quickly exclude half of the data with a single comparison. The binary search algorithm is as follows:

- Base Case: If the list has just one item, then check it and return the result.

- Base Case: If the number in the middle of the list is what we are looking for, then the value is in the list

- Recursion: If the number in the middle of the list is not what we are looking for, then search in either the first half (lower values) or the second half (higher values).

Calling the binary search function recursively on the list subset can either be done by creating a new list or by providing the function with the starting and ending index. The first approach will take more memory.

Here is the code for the binary search.

public bool BinarySearch(int[] sortedArray, int target) {

if (sortedArray.Length == 1) {

// Base case

return target == sortedArray[0];

}

else {

// Find the middle and compare

var middle = sortedArray.Length / 2;

if (target == sortedArray[middle]) {

// We got lucky and the middle was the match

return true;

}

else if (target < sortedArray[middle]) {

// Search the first half (index 0 to middle-1) and return the result

return BinarySearch(sortedArray[..middle], target);

}

else {

// Search the second half (index middle to end) and return the result

return BinarySearch(sortedArray[middle..], target);

}

}

}

...

Console.WriteLine(BinarySearch(new[]{1, 3, 6, 18, 20, 25, 34, 38, 89, 95, 99, 100}, 89)); // true

Console.WriteLine(BinarySearch(new[]{1, 3, 6, 18, 20, 25, 34, 38, 89, 95, 99, 100}, 1)); // true

Console.WriteLine(BinarySearch(new[]{1, 3, 6, 18, 20, 25, 34, 38, 89, 95, 99, 100}, 17)); // false

The performance of this recursive algorithm is O(log n) because we are excluding half of the list with each comparison.

Key Terms

- base case

- The scenario that will terminate (or stop) the recursive calls. If this is not designed properly, then the recursion will run forever.

- memoization

- The technique of remembering previous results found through recursion so that repetitive recursion can be avoided.

- recursion

- The calling of a function with the same function. This can be used to solve problems by identifying a solution which is written in terms of solving the same problem using smaller values. A base case is needed to ensure that the recursion eventually stops. The base cases are solved in the function without using recursion.